Our whole life can be illuminated by Moses’ journey of prayer, who learned to pray and exercised it. It applies to us as well, in a progressive passage of maturation.

Moses is presented as the model intercessor. We already feel very close to us, as pastors of the Church. But his prayer is a journey, an itinerary. I felt this to be very significant for this period in which we are living, although we cannot or perhaps should not approach the various stages of Moses’ life in an excessively analogical way to the stages of this pandemic. Rather, our entire lives can be illuminated by Moses’ journey of prayer as he learned to pray and exercised it. It applies to us as well, in a progressive passage of maturation.

The burning bush (Ex 3:1-6)

An image par excellence of contemplative life, it actually stems from a failure. Moses finds himself in the desert because he flees, having wanted to assert himself by force and arrogance. Moses in Egypt said, “This is who I am” … however, he does it with violence and intolerance. Until he found a power stranger than himself, and everything collapsed. Rambling in the desert, he rebuilt his life, but in reality, the great question remained within him, “Who am I really?

Perhaps we experience something similar with the surprise of the first lockdown, in the sudden and radical closures that displaced us. For to leave usual actions and traditional services, which gave us an identity – sometimes not too reflected, sometimes even violently affirm, “this is me, this is us…” we found ourselves faced with the cruel but necessary question, “Who am I really?”

What saves Moses is that he does not cower within himself to seek the answer. But he goes further, which means into the desert in an even more radical way. He fled from his violent past, but not from the travail of the question, from the aridity of doubt: he lets his thirst emerge. Moses goes further, leading his own sheep, at least as far as they followed him, exploring new, unknown terrain, outside the usual, and even risky boundaries. It is the desire for more, it is the search for God that is hidden in the anxiety and anguish of life that is not satisfied.

There, prayer was born, which is a movement towards God. God called him. But Moses answered because the rock of his heart was already thirsty, ready to be torn apart. The first stone to be broken is not that of Massa and Meriba (Ex 17: 1-7), but that of his heart, from which the water of life slowly gushed forth.

Our first lockdown may have had the connotation of a desert, and we were left with fear and also helplessness. What do we do? What do we do in the face of the barrenness of a frustrated custom, of an unhinged habitual practice? Have we reaffirmed our “I” by repeating, even with technological means, habitual practices that gave us securities? Had we preferred to cower within our fears and frustrations, sustained by the “good excuse” of having to defend our health? Or had we risked an encounter with the Beyond, opening ourselves to the question that underlies an authentic dialogue with God, “Who am I?” and therefore “who are you?”

The Sinai (Ex 19, 1-8)

God reveals to Moses his own name (Ex 3:13-15), and thus reveals to his servant (cf. Deut 34:5) and friend (cf. Ex 33:11) his identity. In prayer, Moses slowly learns to understand who he is, because we are ourselves only in relation to God, and by situating ourselves before Him in the right place. Moses is “God’s man of trust” (Nm 12,7) par excellence, and the confidence with which he establishes a relationship of dialogue with Yahweh is even scandalous. The objections to the call, the spontaneity of the dialogue, even the nerve of the intercession, or even of the ‘unloading of barrels’ (‘it is YOUR people, the ones who complain all the time’ – cf. Ex 32, 11-14): here we see a relationship capable of bringing out the personality of the praying person in all its facets. Prayer makes truth of itself, as well as of God.

Because with God you can talk about anything, and you can avoid spending unnecessary energy hiding behind the masks of complacency. Sometimes it happens that people ask what to do with distractions in prayer…and I wonder that too. In times of pandemic, it’s hard to pray about the Word without constantly being shot through with worries and fears. Which certainly affects others, but has roots in myself. I have to be honest: death is scary to me because it’s my own death at stake. Moses is terrified of putting himself on the line because he fears bad things, he fears for his life, he fears failure… That’s how I am, that’s how we may be. But God is interested in all of this, and He does not shy away from dialogue. On the contrary, He puts Himself on the line with all of Himself.

Sinai, the high mountain, is the setting par excellence of the dialogue between the two: God gives access to Himself to the believing man, allowing him to cross unprecedented thresholds, even unveiling His own glory (cf. Ex 33:18-23; 34:5-9). There is an incredible paradox in the prayerful dialogue of Moses with Yahweh: one has the sensation that for many traits it is rather God himself who prays and invokes Moses to give him a hand. Not only, it is God who gives Moses the best of Himself, from His people (of whom He is so jealous) to the Laws that He Himself has written and imprinted in the heart of man. God reveals His own secrets to Moses, He even entrusts Himself (the Name). Just when Moses shows himself to be so hesitant (stuttering) and fragile. Moses’ strength does not come from his own talents, but from this relationship of mutual trust (!) that God progressively establishes with him.

Who knows, in the uncertainty of the quarantine, and especially in phase 2, in which we did not understand (and do not understand) well what we can do and what we cannot do, where did we learn to rest our security and our trust. Have we sought guarantees and assurances, or have we trained ourselves in patience and profound dialogue with God, who is meddling in our affairs and wants to give us the traces of His presence at every moment? Who knows if we have learned to recognize the glory of God even in the impermanence of existence?

Amalek (Ex 17:8-13)

I have insisted a great deal on Moses’ personal relationship with God, because there can be no prayer of intercession if there is not this radical attitude of vital trust in the One to whom one turns. In the war against Amalek, Moses deploys all the human resources available (“Choose for us some men…” – v. 9 – he says to Joshua, the fighting leader), but then he puts himself at stake with prayer. Nothing magical, nothing superstitious, but an unshakable certainty that God has something to do with our affairs. Life is a battle, but we have a good ally: this is what Moses seems to be saying with his hands raised on the top of the hill, “holding the staff of God” (v. 9).

At the stage we are in now, it seems that prayer for others becomes increasingly important. Just now that the poetry of heroism has passed (think of nurses and doctors hailed in the months of the lockdown and now still on the front lines without the support of the rear guard) and the contradictions of life are more evident, which doesn’t really seem to assure that “we’ll come out of this better off,” taking care of others through prayer seems more urgent than ever. Free prayer, not measured by verifiable results.

Moses’ prayer of intercession is a high and low of success and fatigue, of grit and weariness. The hands stay up, then fall, as do the hearts, sometimes enlivened and charged, other times dejected and sad, perhaps because of news that touches us closely (because we remain men, though we are shepherds… indeed, we hope for more men, because shepherds!). Intercessory prayer is not like Harry Potter’s magic wand, but a powerful magnet that helps us move our gaze towards “things up there”, to realize – and help us to do so – that’s what matters most is beyond. That is, deeper.

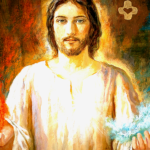

The raised hands of Moses are an announcement of the open arms of Jesus on the cross. This means that our prayer for others is an icon of the offering of our life, it is a support for our daily giving of ourselves in the small things of our mission, it is a constant shifting of the center of gravity from the anxieties of our “I” to noticing those who are worse off than us and have no one to notice them.

This is not an easy task. Therefore, it is considered to be mommunal. Aaron and Cur helped Moses to pray. This is what we are also doing in these meetings. Who knows if there may not be, within the difficult situation we are experiencing, a renewed and powerful call to rediscover and renew the community dimension of our ministry. Gratuity and unity: these seem to be the most significant traits of intercessory prayer, which by turning our gaze to our brothers and sisters (those we remember and those with whom we remember) allows us not to forget that God is always “our” Father, and never only “my” Father.

“Testimoni” es una revista mensual, publicada por el Centro Editorial Dehoniano, con sede en Bolonia, Italia. Su tirada actual es de unos 4.000 ejemplares. También está en línea.

Es una revista de información, espiritualidad y vida consagrada. Desde hace más de 35 años está al servicio de la vida consagrada con especial atención a la actualidad, a la formación espiritual y psicológica, a la información sobre los acontecimientos más importantes de la Iglesia y de los institutos religiosos masculinos y femeninos.

.